More than one commentator has noted that the California Gold Rush, which began in earnest with the discovery of a gold nugget at Sutter’s Mill, Coloma, on January 24, 1848, wasn’t very lucrative to the hoards of prospective miners that flooded the state. It did, however, bring tremendous wealth to those supplying the commodities that supported the mining efforts. This street wisdom is usually condensed to the phrase, “The guys who made the most during the California Gold Rush were the ones who sold the picks and shovels.”

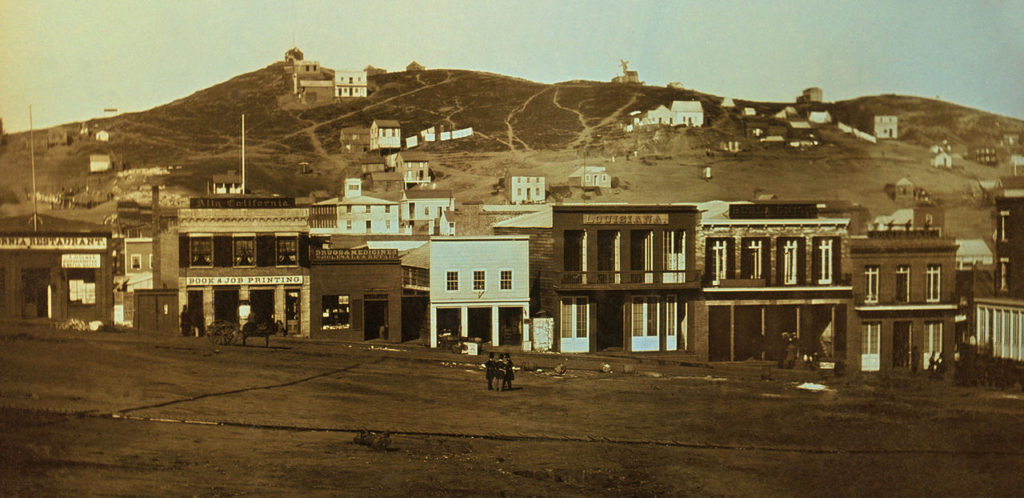

But maybe the more notable takeaway from the gold rush fever is that it energized most of California, turned San Francisco from a a small town into a rapidly growing metropolis, and heralded an immigrant boom in the Golden State that continues even today.

An excerpt from an article on history.com, 8 Things You May Not Know About the California Gold Rush, illustrates this point:

Before John Studebaker built one of America’s great automobile fortunes, he manufactured wheelbarrows for Gold Rush miners. And two entrepreneurial bankers named Henry Wells and William Fargo moved west to open an office in San Francisco, an enterprise that soon grew to become one of America’s premier banking institutions. One of the biggest mercantile success stories was that of Levi Strauss. A German-born tailor, Strauss arrived in San Francisco in 1850 with plans to open a store selling canvas tarps and wagon coverings to the miners. After hearing that sturdy work pants—ones that could withstand the punishing 16-hour days regularly put in by miners—were more in demand, he shifted gears, opening a store in downtown San Francisco that would eventually become a manufacturing empire, producing Levi’s denim jeans.

The immigration surge spurred by the gold rush brought some 300,000 new residents into California by the mid 1850’s. It also drove many residents of the state to temporarily abandon their jobs and homes and leap into the gold rush madness. This flight of workers made things difficult for those businesses that needed workers, such as the vinyards around the state, prompting California to pass it’s first act of legislation to contend with the labor shortage.

Nicknamed the Indian Indenture Act, which was, in fact, the very first legislation that the state passed, cruelly stripped California’s Native Americans of most of their rights. It allowed any white man to identify a Native American as vagrant, lazy, or drunk, which would permit a marshal or sheriff to arrest and fine him. Since most Native Americans could not pay theses fines, a week’s worth of their labor would be auctioned off to the highest bidder, who would then pay the fines. The Native Americans couldn’t protest against their treatment because the law also prohibited them from testifying against white men in court.

This frenzy caused by the lure of gold-rush riches has an analog in the get-rich-schemes extended to writers.

Peddling the Secrets of Quick Riches

If you’re expecting to earn huge amounts of cash as an indie author on your first book, you’re playing the wrong game. The odds are about on par with walking into a casino, feeding five dollar bills into a slot machine, and expecting to hear a chorus of bells signaling a payout sufficient to pay off your mortgage. Nonetheless, the pick-and-shovel sales folks will point to those examples of someone who earns a six-figure income selling their books. It’s kind of like the real estate broker who creates a course about getting rich in real estate or the market expert who supposedly teaches others the tricks for making a fortune buying and selling stocks or the video professional who has a formula for getting rich creating video ads for clients. In each case you have to ask the question: if these guys are so successful in their particular trade, why aren’t they making their own fortunes selling real estate or trading stocks or creating video ads? Because, the real money to be made is in selling the picks and shovels.

In a Brain Blogger article, The Self-Help Industry Helps Itself to Billions of Dollars a Year, Lindsay Myers explores that psychological drive for self improvement that propels an entire industry.

Self-improvement represents a $10 billion per year industry in the U.S. alone. In addition to high revenues, self-help also has a high recidivism rate, with the most likely purchaser of a self-help book being the same person who purchased one already in the last 18 months. This begs the question of how much good these self-help books and seminars are doing for consumers. If they are so effective at solving our problems, why do they usually result in a continuing stream of self-help purchases?

The Long Tail

The takeaway of this story isn’t that writing a book is a pointless endeavor and that you probably won’t succeed, so why bother? The point is rather that writing is hard and you had better like doing it because it’s going to take a lot of words before you see much in the way of earnings. The Author Earnings report, which used to provide fairly optimistic figures on the shape of the industry, especially from an indie author perspective (many of whom contributed to the yearly data, helping formulate a clear picture of indie success), appears to have expired. Equally depressing, the figures from the latest Authors Guild survey show a substantial dip in median author earnings, reaching a historic low of $6080 annually in 2017. This is equivalent to a 42 percent reduction over the last decade.

I guess in an ironic way this article fits into the self-help genre. It’s a pretty small subcategory, however: Don’t expect to get rich writing a book but if you write it, write it well. The cautionary admonition: don’t cast your lot with those miners hoping to strike a fortune, panning away daily with visions of dollar signs spurring them on.

Anne Lamott in her book Almost Everything says it with much more aplomb:

If you do finish what you’re writing, you will probably not sell your book, although you may, for much less than you were hoping (or deserve). No one cares if you continue to write, so you’d better care, because otherwise you are doomed.”

The pithy excerpt continues: “If you do stick with writing, you will get better and better, and you can learn the important lessons: who you really are, and how all of us can live in the face of death, and how important it is to pay much better attention to life, moment by moment, which is why you are here.”

In his Masterclass, Steve Martin teaches comedy, Steve said: “I was talking to some students one time about acting and they were saying things like, ‘How do I get an agent?’ and ‘Where do I get my head shots?’ All this practical stuff. . . I just thought, ‘Really, maybe the first thing you should think about is ‘how do I be good?'” This basic challenge recurs in many creative fields—resisting the temptation to start selling yourself before you’ve honed your skills.

Realistically, you might want to consider taking a different course, looking toward a long-term sustainable career as an author, much as the successes in California grew from those who built businesses, established roots, contributed to a community, and worked toward establishing a thriving, meaningful life on the western fringe of the country.

The ferocity of the best-selling book dream has fueled a lot of writer’s programs and online courses and ten-step formulas. This isn’t to say that there is no value to the programs, only that the value may be getting people engaged in the art of writing and the craft of marketing. Gaining that forward momentum can help get words on pages. The question is: are those words any good? Focus on what is real, writing well, not the fleeting promise of a misty dream somewhere down the road (as Gatsby did).

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch our arms further . . . And one fine morning—”

Now, if you really want to achieve success as an author and gain new skills, I am just about to release my comprehensive training course on the absolutely true, totally verifiable secrets of writing, including a segment that contains translations of inscriptions from within the tomb of Tutankhamun demonstrating the power of symbols to captivate your audience.

Just kidding. Write on. . .