It started with a memory—one insistent incident that begged to be revealed. I had the makings an excellent short story. However, as the fragments of memory coalesced, I realized that this incident was not a turning point or milestone, but a catapult that rocketed me into an alternate future. What led to this change? And what was the outcome? The short story has stretched into a four-year project.

Memoir writing carries its own set of expectations. It must be true, with a host of real characters. Also, you can’t overlook the fact that the story will likely affect others who were featured in your narrative..

I don’t want to skirt events due to possible protest, and I will check with the people I’m writing about. Changing names might be a solution. However, participation in the event could still make people recognizable to their friends and neighbors. For now, my job is to go for it, write it all down, finish the story, and then employ necessary tweaks. Common sense plays a big part in avoiding lawsuits.

A memoir covers a specific expanse of time or an event, as opposed to an autobiography, which covers a lifetime. Anyone who has an interesting story to tell could write their own memoir. The story could be written for yourself, as in a journal, for family and friends, or written with an eye to publishing.

To write a memoir, no matter who the intended audience, the same writing rules apply. Show, don’t tell, and provide powerful descriptions that spark the reader’s imagination. Also, build strong characters. Think about the people that you are portraying, their manner of speech, appearance, habits. They’re real people. Make them real on the page.

Time and place also figures prominently as a character. A good sense of the era will plunge readers into their own imagination or memories. Each reader is a partner in your story. Each reader’s vision of the scene carries them back in time. You provide the road map through the era, and readers collaborate, adding richness with their own imagination.

My story delves into my family life in the 1950’s and 1960’s. I’ve chosen to write each chapter in a short-story format, with a thread connecting them to the theme of the book.

Of course, the theme is the heart of the matter.

In the case of my family and many others of that era, “Nothing’s wrong” was the go-to attitude. This maintained the prevailing veneer of the Leave it to Beaver fifties life. Beneath smiling faces and Sunday dinners, something was wrong.

The oddities of the fifties and sixties eras are both disturbing and hilarious, and I’ve explored this as a backdrop to my story. Here’s an excerpt from the work-in-progress.

Mutants and Communists

America sought the help of its citizens through radio and television announcements. “America needs you to keep a watchful eye. Report suspicious individuals or unusual behavior to the authorities. Your neighbor could be a communist. even your postman…”

These communists could be anywhere. Also, there were bombs to look out for. Drills started up at school.

“When you hear the siren, children, Immediately crawl under your desks and stay there until you hear the all clear signal.”

We hit the floor. Miss Fergusson remained seated. Although protected from nuclear blasts, our desks would not shield us from the nasty rain of teacher guts.

All through the fifties talks of communism continued. As children we were on the periphery of adult discussion hearing snippets here and there. Unanswered questions led to unease. Why didn’t Dad build a bomb shelter like our rich neighbor? Are we really safe hiding under our desks? We saw the mushroom clouds on television. People actually sat in lawn chairs with special goggles to watch.

Disturbing movies appeared with a “mutant” theme. “Them,” the first nuclear monster film, showed gigantic irradiated ants. Later, movie goers would be treated to “The Amazing Colossal Man” and “The Fifty Foot Woman.” We never saw any mutants or communists, and no one blew up. There was nothing suspicious in our neighborhood.

And then there was.

Everyone remembers an event differently, and it took me a while to realize that my memoir is about my memories. With that in mind I have made it a point to honor the facts as I see them. I can’t remember exactly what someone said, but I do remember the gist and accompanying emotion. So, I’m comfortable embellishing the conversation and action to carry forward my viewpoint. At the same time, I try to be as accurate as possible. The following is an example of a dialogue from my story.

“Leave my body in the phone booth, call my dad and get out of here.”

Chris leaned forward resting his clammy forehead on the steering wheel. He angled his face in my direction. “I’ve over-dosed.” Blue lips pulled into a weak smile.

Oh my God. My mind raced with the probable outcome. Chris would die, and then selfishly, I’ll be arrested.

“Why can’t I drive you to the hospital?”

“It’s too late.”

Every moment of that incident is seared into my memory. However, I can’t guarantee the accuracy of the dialogue. The visual aspect and feelings conveyed are spot on.

Writing a memoir draws from experience and emotion, sometimes scraping right down to the bone. This isn’t a bad thing. If anything, I’ve found the process intriguing. Like time travel, I’ve met myself at different stages, exploring my younger version’s mindset. I’ve examined the dumb moves, the right moves, and observed the big changes.

This is my catch-and-release program. Having checked out my early motivations, mistakes, and decisions, I’ve let them swim away. It takes courage to delve the depths, but that brings honesty to the story. Readers will relate.

Although life’s stories are personal and close to the heart, a book loaded with drama after drama is exhausting. And, unless you are the character in your own spy thriller, your story won’t ring true.

The reader doesn’t care about what the writer has been through. Everyone experiences rough times in their lives. What the reader is interested in is the story. The writer’s actions, emotions, investigation, vulnerability resonate the human experience. No one is looking for a self-absorbed account of heroic actions or crazy mistakes, just a well written, honest account.

Life is full of highs and lows, comedy and drama. And, as in traveling, a change of scenery and a few rest stops, heightens the experience. Capturing the flavor of the era, sharing embarrassing moments, and funny stories along with drama, fleshes out the journey, adding extra dimension.

Experiences are neatly stored like memory in a computer. Yet, for the writer, accessing these events can be tricky. We can’t just scroll through our documents. When my memories are dim, I sometimes draw a map. Many writers use this technique to piece memory fragments together.

Envision the place that you wish to write about and make a map on paper. Where was my house? Who lived next door? What did the walk to school look like, or the short cut?What do I remember of smells, of hearing? I try to remember as much detail as I can, not only of place but of people. All of a sudden, the file opens and a rush of memory spills onto the page.

Old photos help too. The picture above was taken at a carnival. My sister and I were thrilled when Dad purchased headbands and feathers. Television, especially Saturday morning westerns, flavored all our playtime. And, we took our play seriously. We wanted to be accurate. We wanted to look the part.

Just before Dad snapped the photograph, I leaned toward my little sister and said, “Indians don’t smile.” This reflects the 1950’s westerns well. Not only did we never see Indians smile, we never saw Indians. Native americans weren’t used as actors. I remember in one movie, the actor portraying the Apache warrior, Cochise, had blue eyes.

I shot a lot of kids with my Colt 45 cap gun, my Daisy air rifle, or my rubber tipped arrows. “Bang.You’re dead.” Death in the fifties was neat and tidy. In the old films, when someone was shot, there was hardly any blood. The unfortunate victim grabbed his heart and with his dying breath uttered “You got me, Partner,” followed by the face plant.

I shot a lot of kids with my Colt 45 cap gun, my Daisy air rifle, or my rubber tipped arrows. “Bang.You’re dead.” Death in the fifties was neat and tidy. In the old films, when someone was shot, there was hardly any blood. The unfortunate victim grabbed his heart and with his dying breath uttered “You got me, Partner,” followed by the face plant.

So what’s stopping you from writing a memoir? Not famous? Good. The most interesting memoirs are written by people with a story to tell, not by a famous person writing about friendships with other famous people.

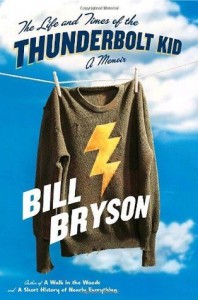

The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid: a Memoir, written by Bill Bryson, is an excellent story about growing up in Des Moines Iowa, again in the fifties era. He brings to life the oddities of his family life. His well-written story places the reader right at the table alongside his family, poking at a plate of charred dinner. Bill Bryson, has written numerous books. Still, he isn’t what I would call famous.

Kay McKracken, author of A Raven in my Heart: Reflections of a Bookseller, penned a story of the unusual events which occurred when she opened a bookstore in a small town. Raven lore and a bit of magic provides a curious support for Kay. Her small selection of books on the occult, myth and magic, becomes the focus of an ultra-right religious group. They picket her store, leaving white crosses on her windows, accusing her of witchcraft.

There are odd ducks in every community. Craziness, conflict, kindness, generosity and stinginess abound. While reading Kay’s book, I was reminded of similar characters from my own past.

There are odd ducks in every community. Craziness, conflict, kindness, generosity and stinginess abound. While reading Kay’s book, I was reminded of similar characters from my own past.

In writing my memoir, I’ve discovered answers, and asked questions that have no answers. I’ve taken a look at my building blocks. Some are solid and perfectly aligned. Others jut at odd angles, and the foundation is riddled with cracks. Hey, that sounds self-absorbed. For me, the writer, it is. The trick is to tell the story and avoid analyzing. If it’s an honest portrayal, the reader will be drawn into the story.

If you have a story to tell, why not give it a go? Perhaps like me, you might begin by writing a short story about an incident. But, watch out. Once the memories start to flow, you may find yourself writing a book.